The Future Favors the Curious

If you’re a designer in the market for a job right now, you probably feel behind the AI wave already, and you’re wondering if the skills you’ve honed in your career are even useful anymore. One of the benefits of being an oldster in this field is that you begin to see patterns in everything, and I’m here to tell you that this pattern has happened many times before and there is a clear way through it as a designer.

In 1995, halfway through college, I determined I was going to be a designer. At that time, 99.99% of “professional designers” had no experience designing anything for the internet. You could have tasked some of the most accomplished designers at the time — Jony Ive, Paula Scher, David Carson, Paul Rand, Massimo Vignelli — with creating a simple 468×60 banner ad and none of them would even know what you were talking about.

Over the next five years, the world would discover what banner ads and the internet were, but most experienced designers stayed put in print, television, or whatever field they were already comfortable with. The designers who would go on to help shape the internet were from two groups:

- People brand new to the industry

- People who looked forward to starting over and getting good at something new

I was somewhere between the two groups, having spent a few years in print but leaning more into a childhood love for new technology than anything else.

Within a few years, the demand for internet-native designers exploded and created the thriving job market we have enjoyed almost uninterrupted until now. Analog design still produces some of the most amazing creative work on the planet, but the growth of that part of the profession has not been the same.

Running design at Microsoft AI and having done a decent amount of hiring lately, I can tell you that the patterns emerging now are exactly as they were in 1995. There is a giant population of designers who have a bunch of really great skills. Some of those designers will decide they are content doing the same sort of design they have done for their whole careers. Others will decide to learn as much as they can about AI and prepare for an industry that will look very different in 5 to 10 years. Finally, there is another group of people who have no design experience whatsoever but are so enamored with this new technology that they will teach themselves very useful skills in a short amount of time. Do not underestimate this third group as it’s easier than ever to fake it ’til you make it right now.

If you are content in your comfort zone, that’s perfectly fine. If, however, you are looking to lean into what’s next, here are some suggestions.

⇗ The Rise of Dopamine Culture

"Here’s where the science gets really ugly. The more addicts rely on these stimuli, the less pleasure they receive. At a certain point, this cycle creates anhedonia — the complete absence of enjoyment in an experience supposedly pursued for pleasure."

A spot-on analysis of where we are as a society with our addiction to short-form entertainment and distractions. I really only see one way out of this (for me, at least) that is simple and resolute: ditching the smartphone. I have tried this for periods of time and it's been perfectly fine in my personal life, but once you need to carry a smartphone for work, complete elimination becomes tricky. I've moved back to my iPhone Mini, which helps a bit, but the thing that would really do the trick would be a phone that only did messaging, phone calls, calendar, Teams/Slack, and maybe Maps. I honestly don't even need a camera, though I'd understand that addition.

One year at Microsoft

Last week marked one year at Microsoft for me, and what an unexpected adventure it’s been! I thought I was coming in to lead a a stable of popular, but well-trodden web properties, and I ended up getting to work on a whole lot more, including Windows, Bing Chat, and the company’s biggest bet in years: Copilot.

I usually write a lot about the companies I work at but have held off until now because we haven’t been hiring. Well now we are! We’re specifically looking for Designers and UX Engineers to work on our design system for Copilot. Some of these positions are on my team and based where we have offices (Puget Sound, the Bay Area, Atlanta, New York, Vancouver, Barcelona, Hyderabad, Beijing, and Suzhou) and some are on adjacent teams and can accommodate fully remote work. If you are a Designer or UX Engineer with a passion for design systems and AI, we’d love to chat.

So what has year one been like? The good and the “needs improvement”. 🙂 👇

One of the reasons I decided to join Microsoft was I missed the joy of in-person product-making. I know not everyone feels the same way so I’m not trying to make any broad statements about local vs. remote work, but for me, it has been even more refreshing than I expected. I usually come in 3-4 days a week, while others on the team are anywhere from 0 to 5.

It’s funny, sometimes I will wake up on a Monday and think to myself “ahhhh, this is going to be a chill work-from-home day” and by the end of the day, I realize I’ve been staring into a screen on video calls for almost the entire day and how much that slowly saps my energy. Meanwhile, in-person days are filled with walks, whiteboarding, and energizing sessions with some of my favorite teammates I’ve ever had. I realize not everyone feels this way about being in the office from time-to-time, but I do. Even our fierce, interdepartmental karaoke battle helped bring a bunch of teams together who had never met before.

The other great thing about lucking out and joining when I did is that we are embarking on one of the rare paradigm shifts that occurs in technology maybe once a decade. The 1980s were about personal computers. The 1990s were about the internet. The 2000s were about smartphones. The 2010s were about the cloud. And the 2020s will be about AI. The really powerful thing about all of these developments is that they don’t replace each other, but rather they build on each other. AI is the result of everything that came before it. If you got into design to help shape the culture of the world around you, these are the moments you treasure.

These turning points are also wonderful because they give you a chance to reawaken to your Beginner’s Mind. I have learned more in my first year here than at almost any other time in my career. Not only does the pace of technological change in AI force you to build skills as you go, but there are so many amazing engineers, designers, researchers, writers, marketers and other creative people to learn from, that it happens almost automatically.

When I was interviewing here, not even my prospective new boss told me about any of what was behind the curtain. Only during my first week did I find out all we are working on to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more. That is Microsoft’s mission statement, if you hadn’t heard it before. It’s an uncommonly good filter with which we can all ask ourselves every day “does this project actually do that?” It’s quite freeing as it gives you license to question projects at every stage of development.

Another thing I’ve loved about my first year here is that I joined a group that has figured out how to ship very quickly. That also has its downsides, as we have plenty of craft problems to solve, but it’s great working for one of the largest and most established companies in tech and being able to ship within weeks of designing something.

One more thing that’s blown me away is the Inclusive Tech Lab, where we work on new technologies to make our products inclusive to people all of abilities and walks of life. No one experiences technology the same way, and teammates like Dave Dame and Bryce Johnson do a ton of great work to make sure that’s top of mind for everyone.

Finally, one of the unsung benefits of working for a native Seattle company again is that Seahawks stuff is all over the place. Presentations, charity auctions, everyday office attire… you name it. It’s nice to not be the only one with good taste in football teams.

I am no corporate shill, however, so I must also be honest about some of the things that need improvement over here.

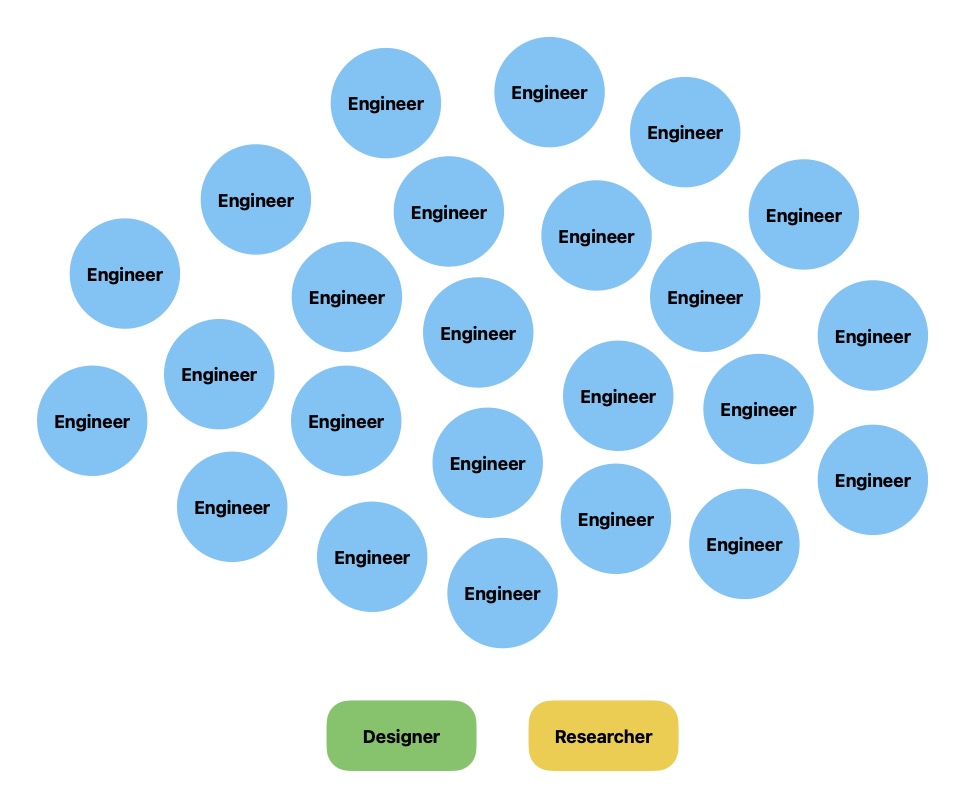

At the top of my list is that Microsoft has not yet fully embraced the role design plays at most other tech companies. We were engineering-driven in 1975 and we are squarely engineering-driven in 2023. The world, meanwhile, has changed in that time. It is no longer sufficient for complex things to work. They must also shed their complexity. People expect the products and services they spend their time and money on to delight. To overdeliver. To give them superpowers. Those sorts of qualities only materialize when you have supergroups building products.

In music, a supergroup is when a singer, a guitarist, a bassist, a drummer, a keyboardist (and so on) who are all at the top of their game come together to create an album. In tech, a supergroup is a researcher, a couple of designers, a product manager, and a Volkswagen Bus or two full of engineers. Up until a decade or so ago, a lot of tech companies followed the model of packing projects with as many smart engineers as they could find and only sprinkled in things like design and research as necessary. I still see some of this thinking in pockets over here. I’m trying to influence things, but it’s a delicate dance, especially when the company has had such enormous success by doing so many other things very well.

I think there are plenty of people here who still feel like being engineering-led is unequivocally good, but to those people I would say that in a modern tech company, design is engineering. It’s no better or worse, but it does have very different leverage in the building of a product.

On the plus side, Microsoft has never had as much design and research talent as it has right now, and we are increasingly looked to by the executive leadership team as lighters of the path. When we go into high-stakes meetings, we always go in with pixels and prototypes, which are uniquely good at cutting through bullshit and ambiguity. As a wise person once said, a prototype is worth a thousand meetings.

There are a ton of amazing designers and researchers who have been here for 10 and even 20+ years whose hard work has led to this moment of evolution for the company, and every day I am in awe of their perseverance.

Next on my list is how often we get in our own way with “procedural goo”. I’ve worked in plenty of large companies including Twitter, Disney, and MSNBC, and have never seen the level of approvals, paperwork, and rules that get in the way of speed and autonomy here. Just transferring someone from within my own org to a slightly different role within my own org took a dizzying amount of effort. At most companies, this would have been about 10 minutes of work: one minute from me and nine from someone in HR trying to navigate to the right screen in Workday.

Then we have acronyms. My GOD do we have acronyms. I actually liked acronyms before I got here! I usually think they are cute. After seeing a new one almost every single day since getting here, I have resolved to never use them either inside or outside of work. I even say “Cyan Magenta Yellow Black” out loud if I have to!

Finally, the last thing on my list — and this is where you come in — is dedication to craft. It is so tempting to try and “science” your way into viable products these days. Build the beginnings of a customer base through rudimentary product-market fit, and then fastidiously optimize your funnel, your game mechanics, your viral loops, your push notifications, and so on and so forth. These gains are not always easy to come by, but they are rooted in ruthless experimentation and allegiance to short-term data. Our north star is at least pretty pure — Daily Active Users — and that metric is usually a good indicator that you’ve made something people like, but doctrinaire allegiance to almost any singular metric can quickly make people forget why we are in this profession to begin with: to improve lives. Or to put it squarely in Microsoft parlance again: to help every person and organization on the planet achieve more.

If you ever find yourself asking the question “how can we increase Daily Active Users?” instead of “how can we make our product better for people?”, you’ve already lost. Metrics are trailing indicators of qualitative improvements or degradations you’ve made for your customers… they are not the point of the work.

Recently, we’ve made some excellent strides in prioritizing qualitative product improvements even when they fly in the face of metrics we care about, and it’s really gratifying to see. It reminds everyone that a product is the collision of thousands of details, and the crafting of these details requires taste.

Designers are often looked to as “owners of craft and taste”, but craft is very much a team sport. It’s not just how things look and feel but also how they work. I very much like how Nick Jones (channeling Patrick Collison) at Stripe put it in this video:

“What we put out there should quite plausibly be the best version of that thing on the internet“.

To do this takes an unbroken chain of excellence:

- An idea that can improve lives if executed well.

- Foundational research to light the path before design and coding begin.

- Rich design explorations and prototyping to make the experience palpable.

- Buy-in to build it at a level of quality that makes the team proud.

- Impeccable UX engineering and UX writing to make sure every detail is dialed.

- Well-conceived server-side engineering to make it scalable and maintainable.

- Creative marketing to prime people for the experience.

- … and finally, maybe more important that anything else on this list, the will to keep refining relentlessly after the experience is launched. This part is so often neglected as companies rush to build more things.

Some people would look at this list and think “yep, makes sense”. Others would look at it and think “sounds slow and not very agile”. The trick to balancing this level of quality with speed of development is realizing that it’s often more efficient to experiment in step 3 than it is in step 6. This is why so many modern tech companies realize that hiring more designers and researchers doesn’t waste time and money… it saves time and money. With less than a week of one designer’s time, we can produce a wide variety of prototypes to test with real people. Just recently, we created an entire GPT-powered research application without even bothering a single engineer.

Design is engineering.

Finally, a brief note about prototyping. I would argue that the most impactful innovation in the craft of product development over the last 20 years has been the rise of rapid design prototyping. Prototypes that demonstrate an experience are useful not just in usability testing, but also in selling ideas up and across the organization. Engineers hate working on things that haven’t been thought through or “appropriately politicked” yet, and if you can bring them a working prototype that has already been vetted with users and various stakeholders across the company, they will love you for it and work hand-in-hand with you to get every detail right.

Design prototypes are the currency of a high-craft, high-speed product development organization, and they are increasingly the currency of our team.

Alright, back to the hiring. I plan to hire against the entire growing list of products our team is responsible for: Copilot, Windows, Edge, Bing, Start, Skype, SwiftKey, and so much more… but for now, this is a concerted hiring effort centered around Designers and UX Engineers to help build out the emerging design system for Copilot and our suite of AI-powered products.

If this is you, please have a look at the following roles we’ve just posted:

- Designer II

- Senior Designer

- Principal Designer

- UX Engineer II

- Senior UX Engineer

- Principal UX Engineer

We’d love to work with you on the future of design systems at Microsoft!

I’m Joining Microsoft!

Despite living in Seattle for almost all of my adult life, I haven’t actually worked for a local company in almost ten years. Remote work is great in so many ways, but in-person collaboration is what gives me life.

In confident pursuit of that feeling, I’m thrilled to be joining Microsoft to run Design & Research for their Web Experiences organization.

I was Microsoft-adjacent 10 years ago at MSNBC.com in Building 25, but this will be my first time as a blue badge, so to speak. I’m also thrilled to be joining Liz Danzico and John Maeda, who have also started at Microsoft in the last several months. I’ve known them both for a long time and have wanted to work with them forever.

There are several things which drew me to this opportunity, but at the top of the list is the people. Not just Liz and John, but the thousands of teammates in Seattle, Vancouver, Hyderabad, Barcelona, Beijing, and many other cities. There are certainly some great solo efforts in tech, but almost all of the best work I’ve been around has been the result of getting the right people jammin’ with each other. In my first several days here, I’ve already met so many of those people, and I can’t wait to continue the momentum Albert Shum created by carrying the torch for one of the best Design & Research teams in the Pacific Northwest.

The second thing I’m super excited about is the scale of the work. I’ve worked on the largest sports site in the world and one of the largest social networks in the world, but the properties in this group reach well over a billion people. Between the (refreshingly fast!) Edge browser, MSN, Bing, and several other products, Microsoft has quietly built up one of the top five properties in the world in terms of traffic and reach. They’ve also done it with humility, knowing how far they are from being perfect. I also love that so many of these products can and will be so much more as we begin to use some of the technology that’s emerging within Microsoft. In my first two weeks, I’m already overflowing with ideas.

Finally, the other thing I’m most excited about is getting back into the office in a flexible hybrid environment. I’ve worked in-person for most of my career and remotely for the last four years, and where I’ve landed is that everyone’s preferences are different, and it’s just tradeoffs all the way down. Where you land depends on a mix of your personality, your life outside of work, and what type of job you have. For me personally, I very much like being around people and feel like I do better work when I am… but I also like getting back my commute time a couple of days a week and making daily jogging more convenient. Also, Henry (pictured above) enjoys the extra lap time. Microsoft’s hybrid policy is a nice balance, and it sounds like exactly the right setup for someone like me.

Speaking of the exactly right, this also feels — for me at least — like exactly the right time to join Microsoft. The company has been through several distinct eras over the decades, but this feels like the era of re-commitment to the planet. To customers delightful experiences, to employees a great environment, and to the natural world, a smaller and eventually negative carbon footprint.

It’s a new year, and I couldn’t be any more here for it!

How to Automatically Post your Tweets to Mastodon

Over the last several weeks, I’ve gotten in the habit of trying to move all of my Twitter activity over to Mastodon instead. I signed up for Mastodon several years ago, but only now are there enough people using it for it to replace a lot of what you might use Twitter for. Some of your friends are there, some of your favorite bots are there, and some news sources are there. What more do you need in life, really?

I’ve been using Pinafore (along with a user stylesheet I created… feel free to grab it for yourself) to use Mastodon on the web, and a combination of Ivory and Metatext on my iPhone. Ivory looks a bit nicer but Metatext has a Notifications tab that acts more you’re used to it working on Twitter.

If you want to move all of your activity over wholesale, go to town. If, however, you want to keep publishing Tweets on Twitter and have them automatically publish to your Mastodon account as well, this short guide is for you. The entire process should take around five minutes. It’s mostly just clicking around on a couple of websites.

Important: If you do this, the goal should not be just replicate your Tweets and never visit or engage on Mastodon. The goal should be to help you build your Mastodon presence and save you from having to manually double-post. Ideally you quickly get to the point where Mastodon becomes your primary crib.

Step 1: Open a Mastodon account

If you’ve already done this, great. If you haven’t, head to any server you want — like mastodon.social, for instance — and set up your account. You can always switch your server (along with any followers you accrue) later, so don’t stress about the server you choose.

Here Lies Flash

In just a few short days, on December 31, 2020, we will say our final goodbyes to one of the most important internet technologies that ever lived: Flash.

I remember vividly the first time I saw Flash on a computer screen. It was 1997, I was finishing up college, and I had managed to teach myself enough HTML to think about pivoting from print design to interactive design as a career.

Web design, at the time, was a clumsy beast. Most web sites were essentially Times New Roman black text on a grey background with an occasional low-quality image here and there. The “design” part was often just figuring out how to best organize information hierarchies so users could feel their way around.

Once we got bored of basic HTML (there was no CSS at the time), we started doing unholy things with images. We’d set entire pages in Photoshop, slice our layouts into grids of smaller images, and then reassemble everything into a clickable mess. These were dark times.

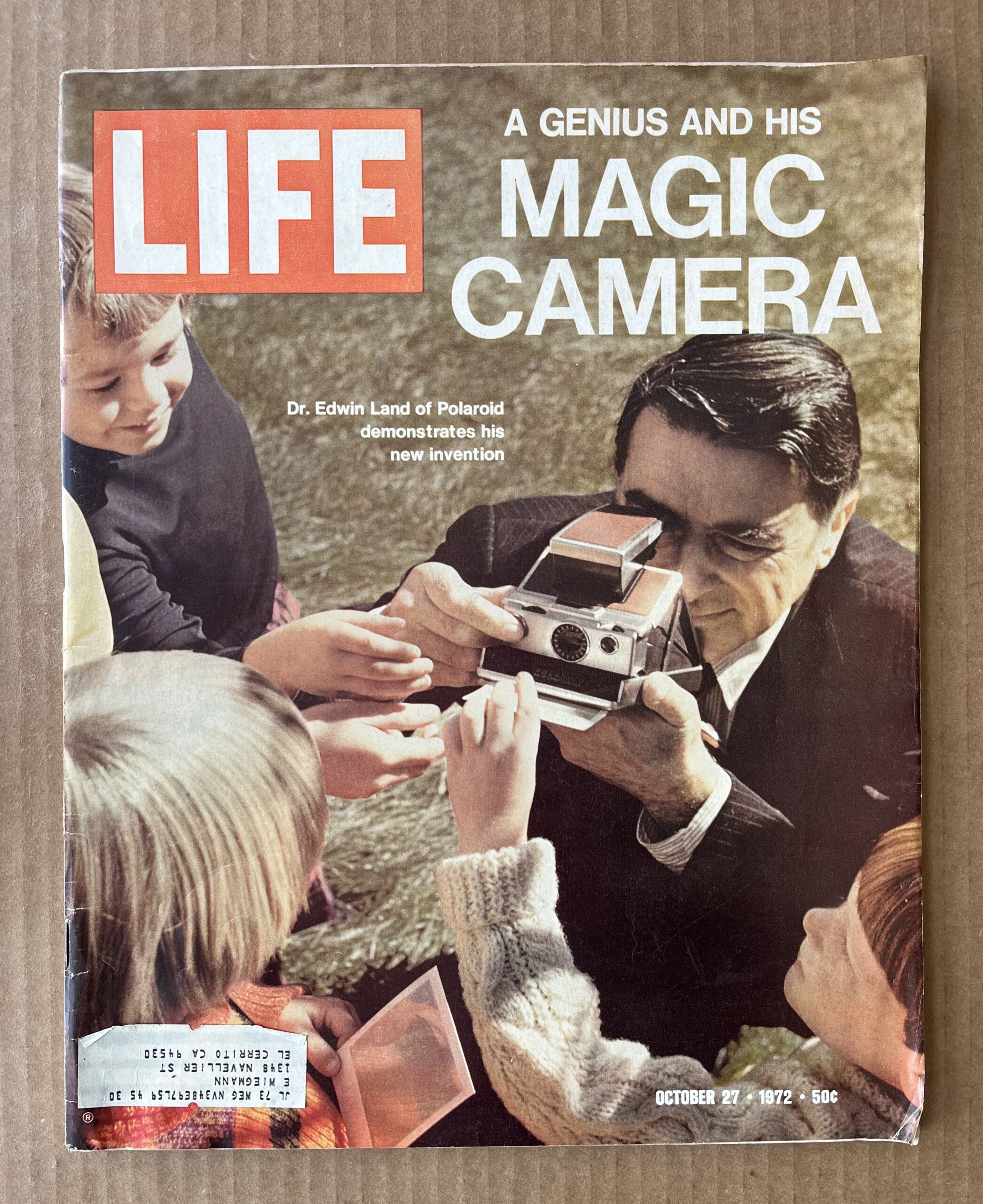

My college, having invented PINE, was considered “on the front edge” of the internet at the time. Here’s is what our site looked like back then:

Even the most beautifully designed sites felt a bit lifeless, and once someone came up with a new layout that worked well, everyone would just ape it. To make matters worse, every new advancement in methods required more convoluted hacking to display correctly across Netscape, Internet Explorer, and every other fringe browser in use at the time. It was a total mess.

Here is the first version of Zeldman.com I could find, from 1998. Amazing for the era, and holds up impressively in a nostalgic, cyber-Americana sort of way, but you can see how limited we were by screen widths, color palettes, and layout technologies.

Then one day in 1997, I clicked on a link to Kanwa Nagafuji’s Image Dive site and the whole trajectory of web design changed for me. It looked like nothing I had ever seen in a web browser. A beautiful, dynamic interface, driven by anti-aliased Helvetica type and buttery smooth vector animation? And the whole thing loaded instantly on a dial-up connection with nothing suspicious to install? What was this sorcery? Sadly, I can’t find any representation of the site online anymore, but imagine the difference in going not just from black-and-white TV to color TV, but from newspaper to television.

Nagafuji’s work was such a huge, unexpected leap from everything that came before it that I had to figure out how it was done. A quick View Source later revealed an object/embed tag pointing to a file that ended in “.swf”. A few AltaVista searches later led me to the website of Macromedia, makers of ShockWave Flash (“SWF”), the technology that powered this amazing site.

I downloaded a trial version and was blown away at the editing interface. Instead of a shotgun marriage of Photoshop, HTML, browser hacks, and a bunch of other stuff that felt more like assembly than design, here was a single interface to lay out text, shapes, images, and buttons, and animate everything together into an interactive experience! It was magic.

After mucking around in the Flash editor (version 2 at the time) for a few hours, I did what every self-respecting web designer would do and immediately set out to find other cool stuff to copy. Over the course of the next several months and years I would find such gems as:

Yugop from Yugo Nakamura

Once Upon a Forest and Praystation from Joshua Davis

Nose Pilot by Alex Sacui

Natzke.com by Eric Natzke

Presstube by James Paterson

Gabocorp from Gabo Mendoza

John Mark Sorum by WDDG

2Advanced by Eric Jordan

NRG Design by Peter Van Den Wyngaert

The Hoover Vacuum Site by Fred Flade

… and of course, everything by Hillman Curtis (Rest in Peace)

(Sadly, much of this work is hard to relive due to Flash already being disabled in many browsers. I’ve tried to point to video demos where possible, but you can also try your luck with the Ruffle plug-in.)

From there, a bunch of us new designers set out to learn more about animation, type, scripting, and everything else that put you at the vanguard of the profession in those days. Flash was the first technology that showed us we could be great.

My initial effort was mdavidson.com, a rudimentary personal site that was the precursor to Mike Industries:

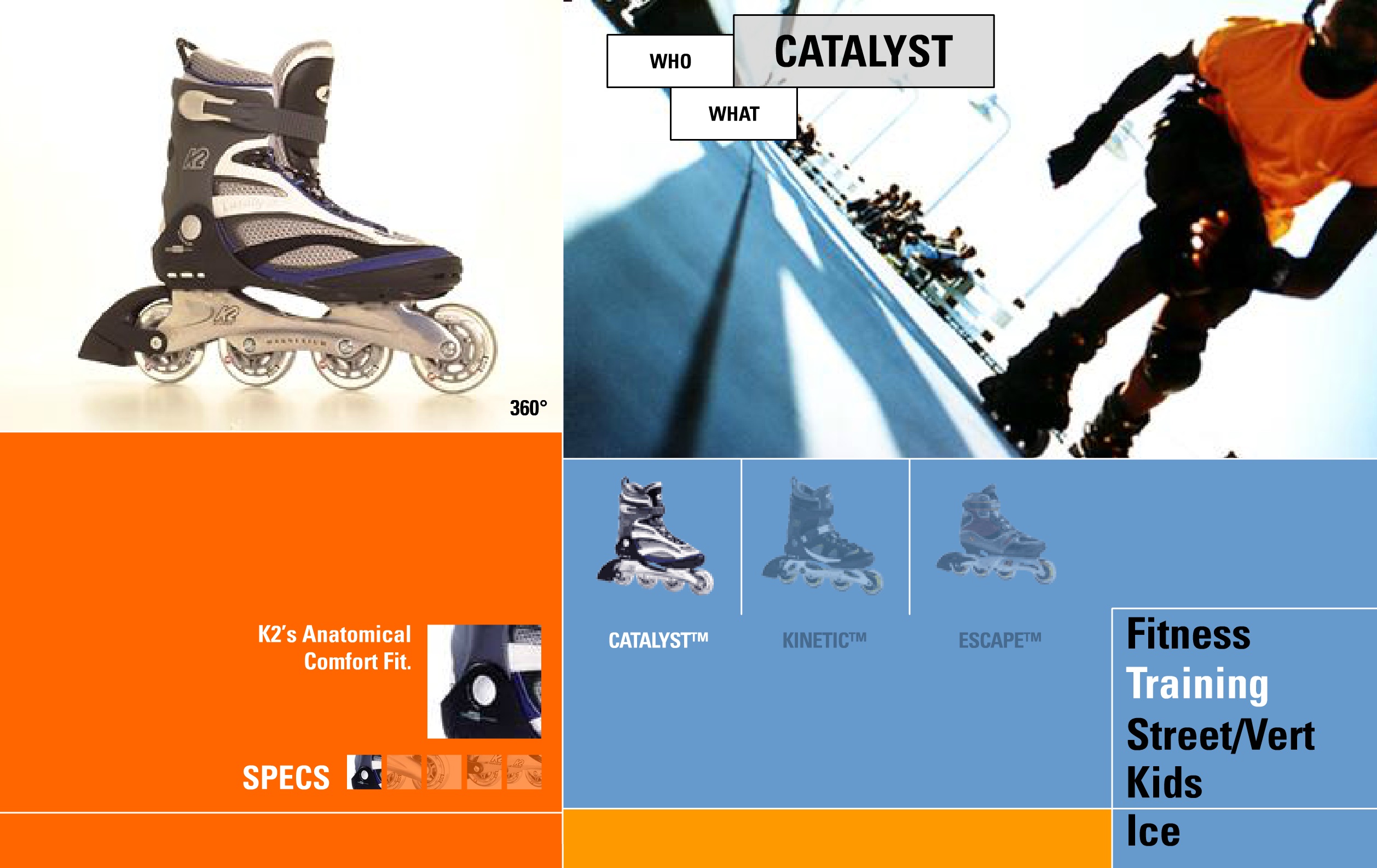

From there, I would move on to design Flash sites and features for ESPN, Disney, K2, The New York Rangers, and dozens of other organizations, never matching the quality of the masters listed above, but always breaking new ground in one way or another.

Other fun projects I collaborated on with my friend Danny Mavromatis included a virtual observation deck for the Space Needle, an interactive on-demand SportsCenter, and a Disney movies-on-demand service fully 20 years ahead of Disney+! All in Flash.

Perhaps the thing that gives me the most joy though is something we built and gave away for free: sIFR. What started as our brute-force attempt to use Akzidenz Grotesk for headlines on the front page of ESPN, turned into a more elegant implementation by Shaun Inman, which then turned into a scalable solution by Mark Wubben and me. We poured hundreds of hours into sIFR not to make any money but just to advance the state of typography on the web.

Over the next several years, sIFR was used to display rich type on tens of thousands of web sites. Although it relied on Flash, it was standards-compliant and accessible in its implementation, so it was the preferred choice for rich type until Typekit came along in 2009 and obviated the need for it.

All of this is to say, the role Flash played in helping transition the web from its awkward teenage years to a more mature adulthood is one I will always appreciate. And we haven’t even talked about its role in game development.

When discussing the life and death of Flash, people often point to Steve Jobs’ “Thoughts on Flash” as the moment things turned south for it. Worse yet, the idea that “Steve Jobs killed Flash”. I don’t think either of those things is actually true.

Flash, from the very beginning, was a transitional technology. It was a language that compiled into a binary executable. This made it consistent and performant, but was in conflict with how most of the web works. It was designed for a desktop world which wasn’t compatible with the emerging mobile web. Perhaps most importantly, it was developed by a single company. This allowed it to evolve more quickly for awhile, but goes against the very spirit of the entire internet. Long-term, we never want single companies — no matter who they may be — controlling the very building blocks of the web. The internet is a marketplace of technologies loosely tied together, each living and dying in rhythm with the utility it provides.

Most technology is transitional if your window is long enough. Cassette tapes showed us that taking our music with us was possible. Tapes served their purpose until compact discs and then MP3s came along. Then they took their rightful place in history alongside other evolutionary technologies. Flash showed us where we could go, without ever promising that it would be the long-term solution once we got there.

So here lies Flash. Granddaddy of the rich, interactive internet. Inspiration for tens of thousands of careers in design and gaming. Loved by fans, reviled by enemies, but forever remembered for pushing us further down this windy road of interactive design, lighting the path for generations to come.

RIP Flash. 1996-2020.

If you feel so moved, pour one out for our old friend in the comment section below.

Machine Learning and Cover Songs

There’s nothing like a great cover.

You’re rekindling angst at a Pearl Jam show and without any warning they go right into a Beatles song. You recognize some David Bowie lyrics on Spotify, and you discover it’s an unrecognizable version of Let’s Dance by M. Ward. You listen to Tiny Cities by Sun Kil Moon several times before you even realize it’s an entire album of beautifully fermented Modest Mouse songs.

How often have you thought to yourself, I would love to hear this person sing this other band’s song in their own style? For instance, I wish I could listen to Mike Doughty sing just about anything.

Over the past year or two, we’ve started to see artificial intelligence begin to approximate that dream (or nightmare, depending on your perspective). First it was eye-opening deep fake videos of past presidents appearing to say things they never said, but now it’s moved on to much more creative and cool endeavors like OpenAI Jukebox. You should read the full description on the site, but essentially they are training models to identify everything that goes into a song: instruments, lyrics, musical style, and a whole lot more. The models are primitive for now, but even at this early stage, they can start recombining things in interesting ways like having Ella Fitzgerald sing a Prince song but in the style of folk rock.

I spent a good part of the weekend messing around in Jukebox, and it’s mesmerizing. It really feels like the beginning of something big, and just as excitingly, something that could get orders of magnitude better within only a few years.

When you listen to it, it almost feels like the first words of a child… or if you prefer, the first song from Jimmy Page.

A lot of the stuff in the library is pretty rough, but here are some of the most interesting ones I found:

- Frank Sinatra introducing Jukebox

- The Greatest Love of All by Whitney Houston re-arranged and sung as Bob Dylan

- U Can’t Touch This by M.C. Hammer re-arranged and sung as Earth, Wind, and Fire

- Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening. A poem by Robert Frost. As read by Dolly Parton, Aretha Franklin, Neil Diamond, or Billie Holiday.

- Some of them aren’t so much “good” as they are fascinating, like this attempt at Brain Damage by Pink Floyd which sounds like a singer who doesn’t know English trying to just sound out the words as best he can.

- Others come pretty close to the real thing, like these Ray LaMontagne and Ryan Adams songs, which sound like they’ve just had a few too many whiskeys.

Everything feels very Frankensteiny right now, but imagine a few years from now when these techniques are improved and expanded. We may reach a point where there is a virtually unlimited universe of concert-quality covers you can create with just a few taps. As a music lover, this is super intriguing, but on the other hand, I wonder how musicians will feel about it. And will their opinions change based on whether we can find a way to monetize it generously for them? I could see some artists rejecting this sort of thing outright because it’s not real music in the traditional sense, and I wouldn’t blame them. But what if you told them that every time their voice was mixed into another song, they made a royalty off of it? That might change some opinions.

This is going to be a really fun space to watch closely over the next few years. Until then, I leave you with another great cover: Metallica’s Orion — by Rodrigo y Gabriela. Incidentally, the header image for this page is from their Masonic Auditorium show in 2015. Pure luck but probably the best photo I’ve ever taken.

Minimum Viable Connectivity

I remember about 15 years ago — before the launch of the iPhone — thinking quite resolutely that internet-connected phones were just a really unexciting transition phase between the desktop internet and immersive technologies like contact lenses and brain implants. We knew where we already were: amazing high bandwidth experiences on the desktop, and it seemed pretty clear where we were going in a couple of decades: even better experiences with no visible hardware whatsoever.

The new class of experiences on mobile phones at the time, however, was uninspiring. Palm Treos with barely functional browsers on them. Blackberries that handled email but little else well. T9 keyboards that were a pain to use. Barely any designers wanted to work on this stuff. It wasn’t very fun to create, use, or even tell anyone you worked on.

When the iPhone came along in 2007, it was the first mobile device that was fun to design for and fun to use for a wide variety of things. As it grew more and more useful, I began to think of internet-connected phones as quite a bit more exciting but still ultimately a transition state to full cyborg land. It seems inconceivable that in 10 or 20 years, we will still be staring down at these glass rectangles instead of directly at the world with whatever augmented reality experiences we choose in between.

As phones have gotten more comically large and the services on them more tragically addictive over the past few years, I’ve found myself wondering if there is more value in letting some of this connectivity go. Clearly smartphones provide a lot of value for us, but what is the true cost of all this convenience? Being able to receive a text from your spouse while you’re at the supermarket is valuable, but the same device that delivers you that text can deliver a social network notification while you’re driving that ends up killing you or others.

Attempting to quantify the large and small harm caused by smartphone use is a big project better suited to places like Tristan Harris’ Center for Humane Technology, but you don’t need to quantify it to admit it’s doing you some amount of harm.

There is no shortage of advice about how to make your phone less addictive. Turn off a bunch of notifications. Flip on Do Not Disturb. Use Black & White mode. Delete social networking apps. It’s all good advice, but for me, having that giant, heavy glass brick in my pocket is a constant reminder of what’s at my fingertips.

What I’ve really grown to want is less at my fingertips.

Minimum viable connectivity.

Wherever I happen to be, I want the least amount of potential digital distractions and appholes around me. It’s no different than the concept of eating healthier. When you want to lose weight, you don’t keep a bunch of junk food in your pockets and just promise to never open it. You remove junk food from your house completely.

Until recently, there was no great way to stop carrying your smartphone with you without giving up a ton of benefits. Over the past two weeks, however, I’ve begun using an Apple Watch without a phone almost all day long, and it’s been great. It’s introduced exactly the amount of digital friction I need in my life and I don’t imagine going back to hyper-connected smartphone world anytime soon.

“The best way to guarantee success is by preemptively engineering systems to reduce friction for positive habits, and increase friction for negative ones.” — Craig Mod, from the great piece I linked to above

I love that I am still generally reachable by phone or text when I wear it. I love that I can still navigate with maps. I love that I can track my runs without third party services and listen to podcasts along the way. I love that I can see when it’s about to rain.

And I love that that’s about all I can do. I don’t mind that texts are a little harder to send. I don’t even mind that there’s no camera. If I’m on vacation in an interesting place, I will surely take my phone, but do I really need to be taking more photos around town? Probably not. This is the point many people will break with me on this whole strategy, but try it. You may be surprised.

In terms of things I don’t like about about this experiment so far, it really just comes down to a couple of flaws with the watch itself: the LTE radio is pretty spotty and the Apple Podcast app is a usability disaster, both on the phone and the watch. Because the radio is weak, you really need to make sure anything you want to listen to is downloaded already, and because the apps are so bad, it’s very hard to ensure that actually happens. You’ll generally have some podcasts downloaded and ready to listen to but they just aren’t always the ones you expected. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Even with those problems, I still feel great about this less-connected road I’m going down. Somewhat surprisingly, I don’t even feel like I’m missing out on anything.

The hyper-connected future will probably still happen, but the form it will take doesn’t feel so inevitable to me anymore. I’ve learned in these two weeks alone that I don’t actually want every distracting digital experience in the world at my fingertips. I only want what is helpful and stays out of the way.

The last time I wore a watch was in high school, and I distinctly remember how excited I was to finally get a cell phone my junior year.

27 years later, I’m just as excited now to do the opposite.

Superhuman’s Superficial Privacy Fixes Do Not Prevent It From Spying on You

Last week was a good week for privacy. Or was it?

It took an article I almost didn’t publish and tens of thousands of people saying they were creeped out, but Superhuman admitted they were wrong and reduced the danger that their surveillance pixels introduce. Good on Rahul Vohra and team for that.

I will say, however, that I’m a little surprised how quickly some people are rolling over and giving Superhuman credit for fixing a problem that they didn’t actually fix. From tech press articles implying that the company quickly closed all of its privacy issues, to friends sending me nice notes, I don’t think people are paying close enough attention here. This is not “Mission Accomplished” for ethical product design or privacy — at all.

I noticed two people — Walt Mossberg and Josh Constine — who spoke out immediately with the exact thoughts I had in my head.

1/ This is a good *first* step. Better than doing nothing. But it’s not enough. I read the full blog post. It makes no mention of disabling tracking how *often* the recipient opens the email. It’s also full of the rationalization that secret tracking is ok in “business” software. https://t.co/c0PbCRLgdp

— Walt Mossberg (@waltmossberg) July 3, 2019

I appreciate Superhuman’s changes, but the problem is recipients don’t know they’re tracked, and it’s still not going to warn them https://t.co/GPfUYVkBMs

— Josh Constine (@JoshConstine) July 3, 2019

Let’s take a look at how Superhuman explains their changes. Rahul correctly lays out four of the criticisms leveled at Superhuman’s read receipts:

Superhuman is Spying on You

Over the past 25 years, email has weaved itself into the daily fabric of life. Our inboxes contain everything from very personal letters, to work correspondence, to unsolicited inbound sales pitches. In many ways, they are an extension of our homes: private places where we are free to deal with what life throws at us in whatever way we see fit. Have an inbox zero policy? That’s up to you. Let your inbox build into the thousands and only deal with what you can stay on top of? That’s your business too.

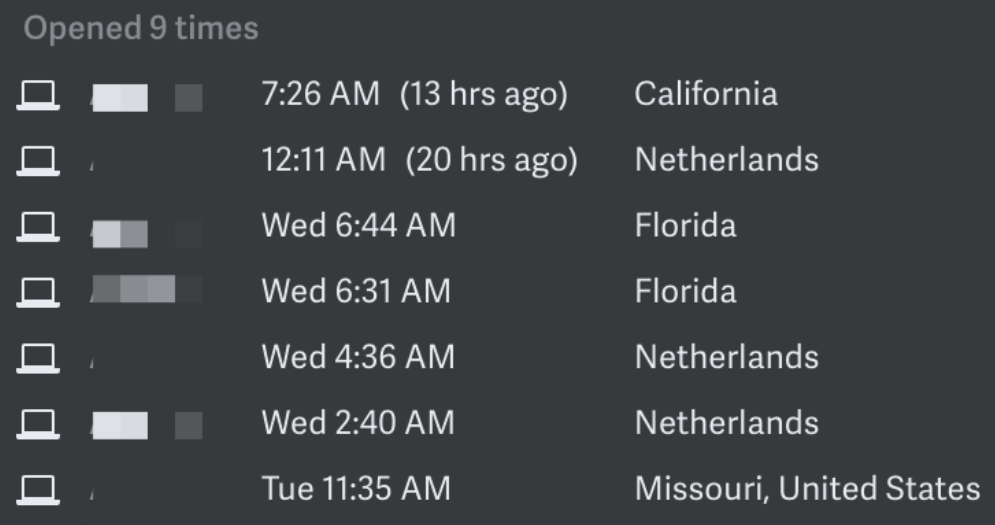

It is disappointing then that one of the most hyped new email clients, Superhuman, has decided to embed hidden tracking pixels inside of the emails its customers send out. Superhuman calls this feature “Read Receipts” and turns it on by default for its customers, without the consent of its recipients. You’ve heard the term “Read Receipts” before, so you have most likely been conditioned to believe it’s a simple “Read/Unread” status that people can opt out of. With Superhuman, it is not. If I send you an email using Superhuman (no matter what email client you use), and you open it 9 times, this is what I see:

That’s right. A running log of every single time you have opened my email, including your location when you opened it. Before we continue, ask yourself if you expect this information to be collected on you and relayed back to your parent, your child, your spouse, your co-worker, a salesperson, an ex, a random stranger, or a stalker every time you read an email. Although some one-to-many email blasting software has used similar technologies to track open rates, the answer is no; most people don’t expect this. People reasonably expect that when — and especially where — they read their email is their own business.

When I initially tweeted about this last week, the tweet was faved by a wide variety of people, including current and former employees and CEOs of companies ranging from Facebook, to Apple, to Twitter:

It was also met critically by several Superhuman users, as well as some Superhuman investors (who never disclosed that they were investors, even in past, private conversations with me). I want to talk about this issue because I think it’s instructive to how we build products and companies with a sense of ethics and responsibility. I think what Superhuman is doing here demonstrates a lack of regard for both.

First, a few caveats: